Prosperity theology in Tanzania

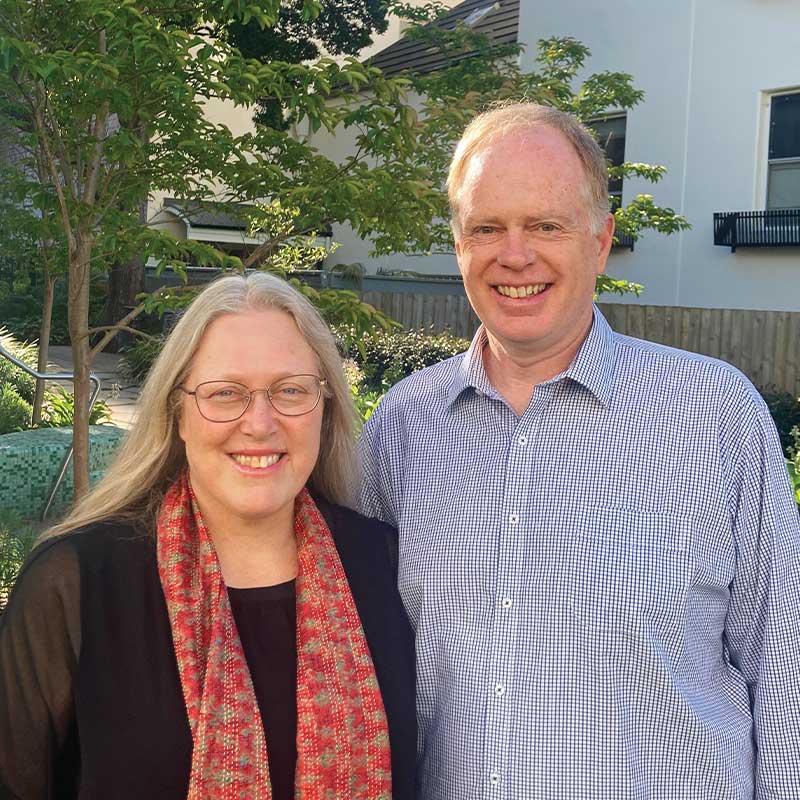

CMS missionary Tamie Davis, soon to return to Australia after ten years serving in campus ministry with Arthur in Tanzania, helps us to see how ‘prosperity theology’ can be about Bible application, not just greed.

Michael Oh, Global Executive Director of the Lausanne Movement, recently said that as Christianity in Africa grows at an astonishing rate, people are “eager to know Jesus, but they’re also asking for one more thing: a job.”[1] According to Oh, the church in Africa doesn’t have an answer to that question. But Islam does, and is growing even more rapidly.

Gospel urgency with a catch

Oh is right: there is an urgency in Africa for the gospel to make a difference in people’s lives. I’ve been privileged during my time in Tanzania to see it doing just that. Christians here in urban Tanzania believe passionately that knowing Jesus makes a difference to a person’s economic wellbeing. They run schools and businesses, teach on leadership and ethics, and they network like only Africans can! These are Africans who do indeed have an answer to the request of African Christians for a job.

There’s just one catch. Their theology is a prosperity theology. By ‘prosperity theology’, I mean they believe that financial blessing and physical wellbeing are God’s will for Christians, and that they can receive these by faith in God.

Prosperity teachings in Africa

You might have heard this kind of theology referred to as ‘prosperity gospel’ or the ‘health and wealth’ gospel. Superficial at best, heretical at worst, it is often held up as the epitome of African Christianity being ‘a mile wide and an inch deep.’ It creates false expectations of fabulous wealth and a life free from suffering. It blames the poor for their lack of faith, and makes God out to be someone who needs to be manipulated in order for him to be generous.

Well, sometimes it does that. Too often. But sometimes it doesn’t.

I’ve used the term ‘prosperity theology’ instead of ‘prosperity gospel’ because there’s a whole heap of teachings in Africa about prosperity and how God wants you to flourish. Not all of them are bad. If, as Oh suggests, the African church needs to have an answer to the African Christian’s request for a job, that will require a theology in which getting a job—a measure of economic prosperity—is a good thing. And good things are what God desires for his people.

A better prosperity theology

Let me tell you about another kind of prosperity theology, the kind we have encountered in urban Tanzania (alongside superficial or heretical versions). In this ‘alternative prosperity theology’, God’s ways for prosperity are not located in some special preacher or a particular prayer technique: they’re open for all people to see because they’re in the Bible! In Proverbs, you can read all sorts of nuggets of wisdom about prosperity; in the stories of the Old Testament, you can notice how people relate to each other and what the consequences are; in Deuteronomy, you learn what God considers to be righteousness; in the gospels you meet Jesus who heals and welcomes even those whom others consider unworthy and raises them up with him.

So if you want prosperity, you have to become a student of the Bible, coming to it humbly and reading it in context.

As you know the Creator better, you are equipped to live well in the world he created. This does not mean things will always be easy for you. You’ve read plenty of stories in the Bible of believers who suffered. Yet it also means that you don’t see hardship as indicative of God’s abandonment. On the contrary, you begin to see that you have a part to play in God’s world. Prosperity becomes not only a matter of prayer but of action: hard work, righteous living, being in good standing with others.

Can you see how this alternative prosperity theology mobilises Christians to both create jobs and remain faithful to God? Can you see how it critiques other kinds of prosperity theologies, while not giving up on the idea of godly prosperity? Can you see how it might empower Christians to form communities and socio-economic structures that can make Christianity a real, viable option for people—instead of asking them to choose between being a Christian or having a job?

Working with Tanzanians towards a better prosperity theology

I do have reservations about this alternative prosperity theology. For example, it tends to treat the Bible as a guidebook or resource, so that it collapses the space between us and God’s Old Testament people. But I can also see God at work here. I can see how it presents God as generous in his revelation and grows confidence in his good words. I can see how it gives people hope and a reason to be active in God’s world without making false promises of a free and easy life. It’s not my alternative to that superficial prosperity gospel, but nor should it be.

From its earliest days, CMS has believed in Henry Venn’s ‘self’ principles, where indigenous churches become self-propagating, self-financing, and self-governing.[2] This has been part of the reason that CMS has invested so heavily into theological education in Africa, that the leaders and teachers of the church would be African! A natural flow-on from this is to become self-theologising, where African Christians can faithfully form their own African theologies that make sense in their context and can respond where there is shallowness or heresy.

In Tanzania we have witnessed God’s people doing just that, by developing their own teaching about prosperity that both counteracts false teaching and empowers God’s people for lives of faithfulness. I praise God that when I see superficial or heretical prosperity theology in Tanzania, there is a Tanzanian critique of it and a Tanzanian alternative to it.

Both Arthur and Tamie Davis have long been involved with African leaders assisting university ministry in Tanzania. What underlay this significant commitment? Read more here.

PRAY

Pray for Tamie and Arthur Davis as they work with Tanzanian Christians to think about what true ‘prosperity’ looks like for them and for the Tanzanian church into the future.

[1] Henry Venn was secretary of the Church Missionary Society (UK) from 1841 to 1873, and one of the foremost mission strategists of the 19th Century.

[2] Michael Oh, ‘How Global Is Your Faith?’, Lausanne Movement. 25 October 2022. lausanne.org/about/blog/how-global-is-your-faith