Two-way learning

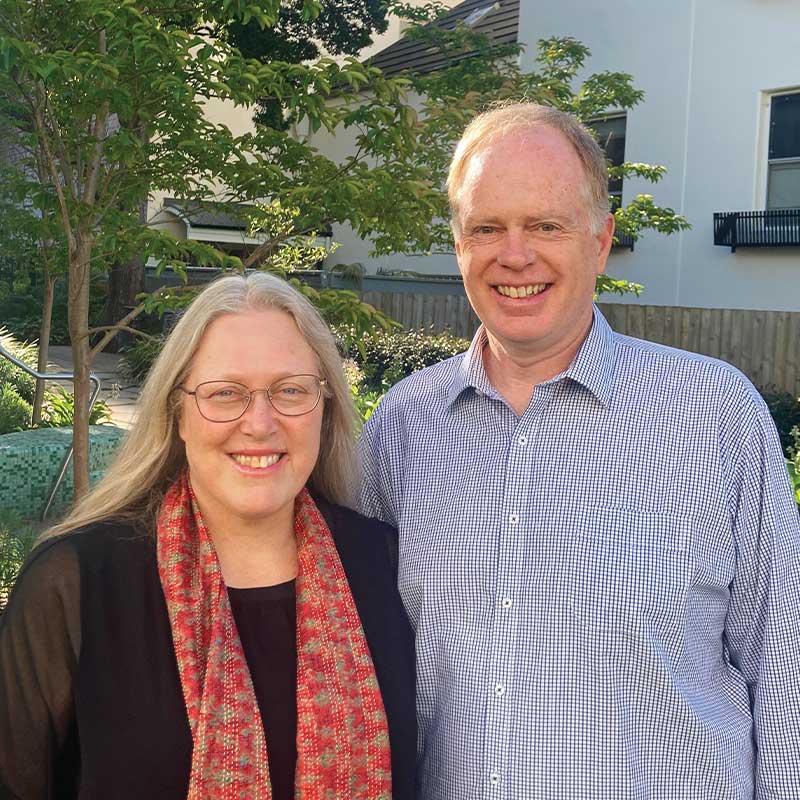

Simon and Claire Koefoed are associate workers with CMS in Darwin. Simon serves as Archdeacon in the Anglican Diocese of the Northern Territory. In this article, he reflects on the power imbalances that exist in Northern Australia, and the ‘two-way learning’ approach that seeks to redress this imbalance.

A power imbalance

For Western culture people like us, ministry in North Australia alongside Aboriginal Christian leaders is confronting. The experience of Western power for Aboriginal Australians across the country will be different in different locations.

In the Northern Territory, a high proportion of the population are Aboriginal Australians, yet it is common for Western culture people to live here and never have a meaningful conversation or interaction with an Aboriginal Australian person.

If that interaction does occur, it is the Aboriginal Australian person bridging all the gaps. The interaction will most likely be in English—a second or third language for many—and the Aboriginal Australian person will be the one conforming to Western cultural norms to make the interaction relatively comfortable.

There is always a power imbalance.

Various activities such as law enforcement, healthcare, education, translation, social, and church work bring Aboriginal Australian people and Western culture people together as ‘part of the job’.

Some of these helping professionals are openly racist and abusive. Many others who genuinely want to help, don’t always help. In fact, they often hurt as they help1. Church workers are not immune to this.

All of this is very confronting.

My vulnerability in language and his vulnerability in literacy meant in that moment of reading the Kriol Bible together, we needed to trust each other, in our mutual vulnerability.

Duane Elmer2 writes:

‘…let’s not be naïve, anyone from the West who enters a new culture or ethnic group has power. Finance, education, resources, technology, relational networks… I’m not so concerned about the fact that Westerners possess power. I’m concerned about how it is exercised…’

In North Australia, we need to be careful and ‘not be naïve’. Western church workers, even in the most remote locations and in the most basic of living conditions, have ‘finance, education, resources, technology, relational networks…’ and more.

In addition, we are often unaware of when and how we exercise this power.

For this article, I was asked to write about the overall picture of Indigenous ministries in the Northern Territory and share some good news stories. We have many good stories to tell.

But good news stories amongst Aboriginal Australians in the Northern Territory are not straight forward. To hear them properly we will need to suspend judgment and

enter them with a spirit of curiosity and humility3.

A Nungalinya graduation

For Aboriginal Australian people, cultural knowledge is the primary commodity4. Acknowledging and celebrating the transfer of knowledge between patron and client, by ceremony and initiation, is culturally normal.

So, things like ordinations and Nungalinya College graduations are a very big deal!

In the last four years I have been privileged to witness many of these good news stories. Recently, I was invited to participate in a Nungalinya graduation, filling in for Bishop Greg Anderson, who was on sabbatical.

I was looking forward to the graduation because two of these Anglican graduates—Darryn and Edwin—have been my cultural mentors and taught me Australian Kriol5.

For Darryn and Edwin, graduating with Cert IV in Theology and Ministry is a significant achievement. The knowledge they have gained through years of study has been beneficial to the congregations and communities they lead.

This is a good news story!

My role in the ceremony was to hand the graduating students their certificates and pray for them in their ongoing ministries. I felt honoured to do this, and in practical terms it was an easy job.

However, it was not entirely straight forward. I could easily make cultural and missiological errors in presenting these certificates. As I sat waiting for the ceremony to begin, I wanted to carefully gather my words.

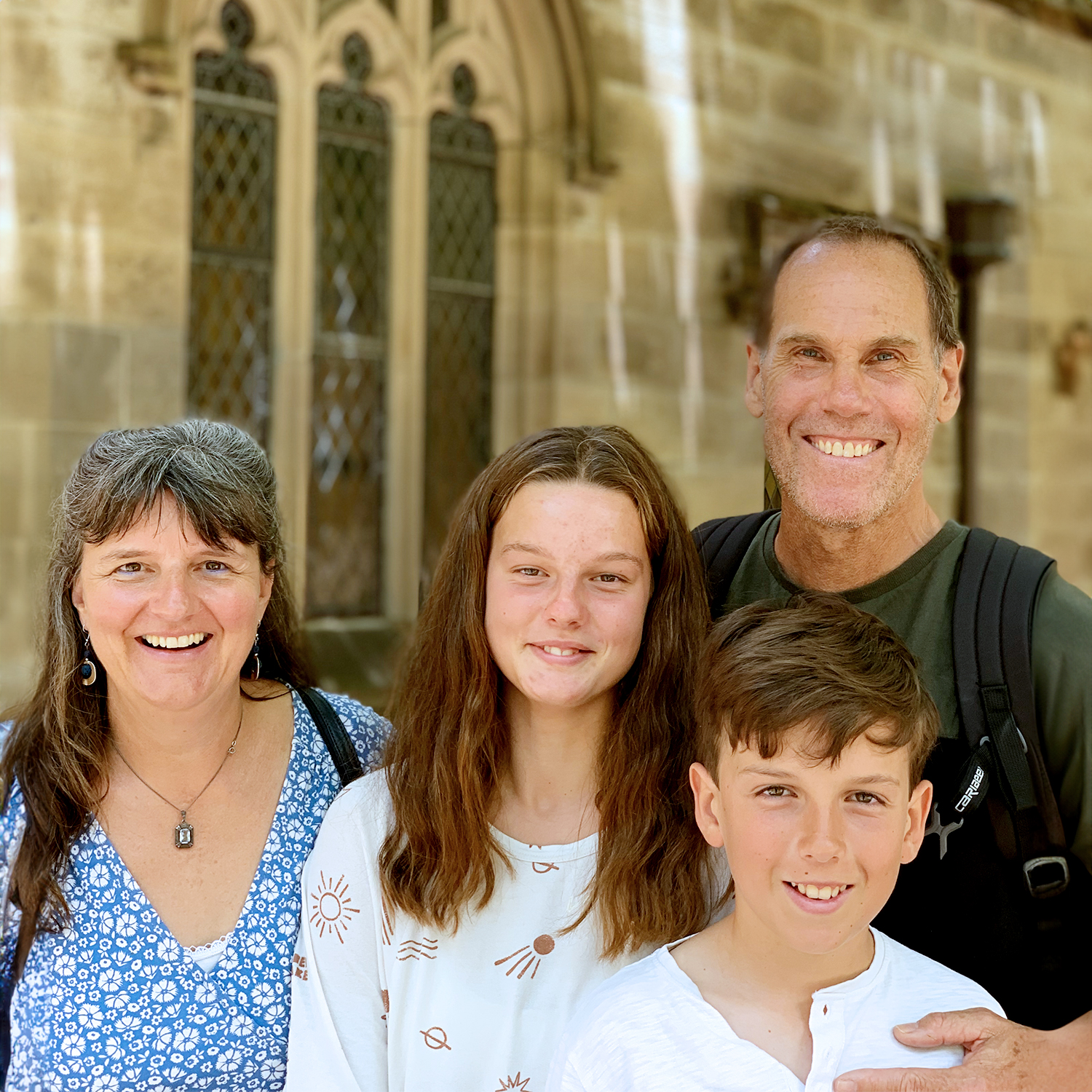

Edwin, Simon and Darryn pray at the Nungalinya graduation ceremony.

The Ministry Development Team (MDT) I work with wrestles with these sorts of cultural dynamics regularly in our ‘TeamShare’ meetings.

The MDT is a group of church support workers committed to supporting Aboriginal Australian church leaders as best they can, offering help without hurting. These meetings are a place where we bring challenging cultural interactions to share and learn together.

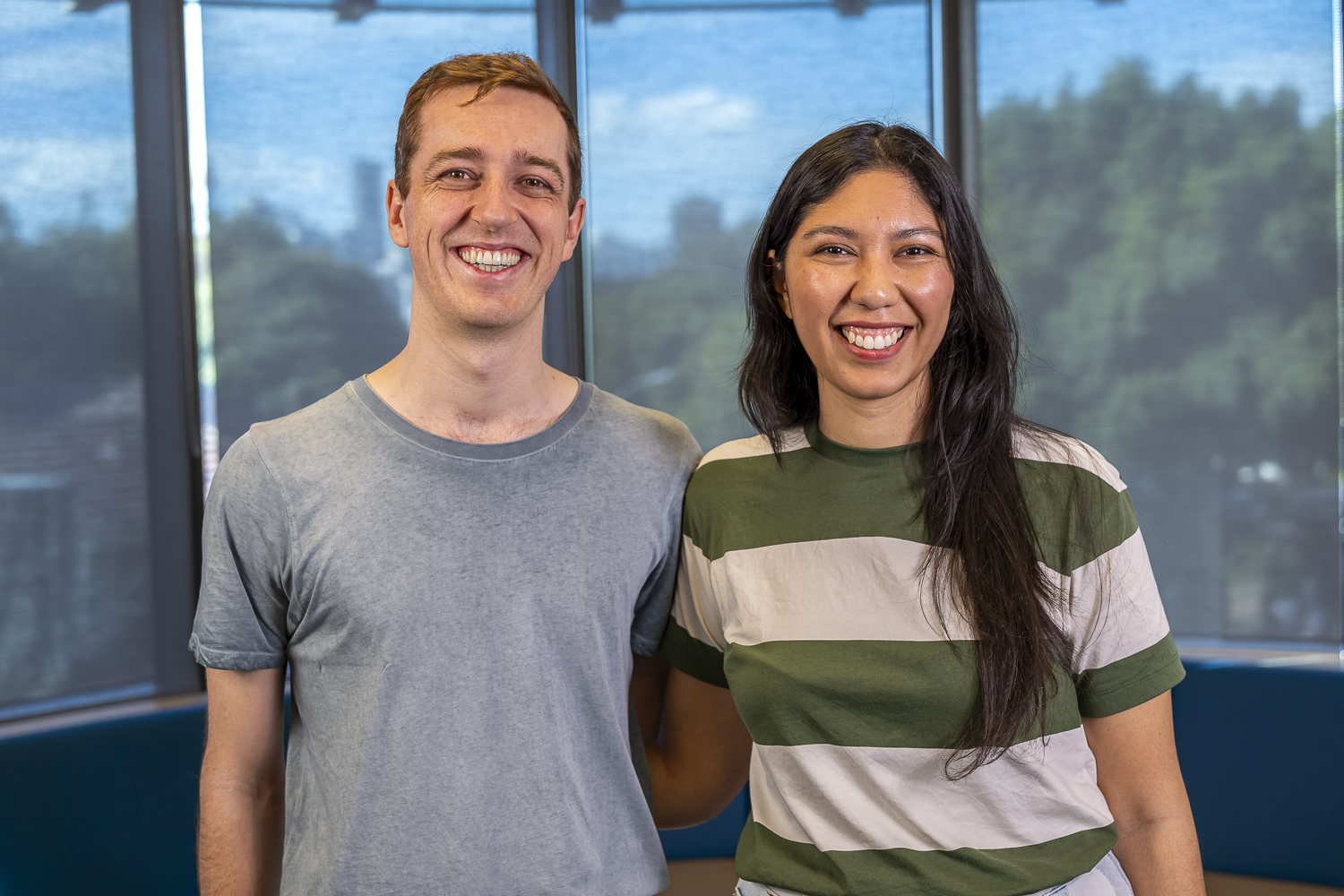

CMS missionary and MDT Team Leader, Josh Mackenzie, has thought a lot about the very challenge I faced at the graduation. Josh writes:

“As Christians, however, we should avoid the mistakes of European patrons who have acted upon Indigenous people as if they were passive clients, and instead hold at the very core of our actions the collaborative approach of servant leadership. As servant leaders we recognise that patronage relationships are by nature reciprocal, and that we need to be ready to receive as well as give.6”

With this sort of thinking in mind, as I gathered my thoughts, I was able to add a few simple words.

I noted to the gathered students and supporters that it was “A bit funny for me, the student, to hand certificates to my teachers”. I wanted to reinforce Nungalinya College’s ‘both ways’ approach to learning7.

I am grateful to CMS for the cross-cultural ministry training and preparation to think carefully about these issues, and for the ongoing collaboration of the MDT Anglican Diocese of the Northern Territory.

Mutual vulnerability

My previous example of the Nungalinya graduation is full of tension. It is right and proper for the Bishop to present graduates with certificates. In fact, the graduates might feel shame if the Bishop (or his delegate, in this case) did not honour them with participating in this ceremony.

On the other hand, it would be naïve to not recognise the power imbalance in the room8.

There were two other Catholic and Uniting Bishops presenting certificates to their respective graduates, and the former principal of Nungalinya read the students names as they all came forward. All four men—including myself—are of Anglo-European background.

There are many other stories that are not publicly visible. I will share this one for a point of contrast to the one above.

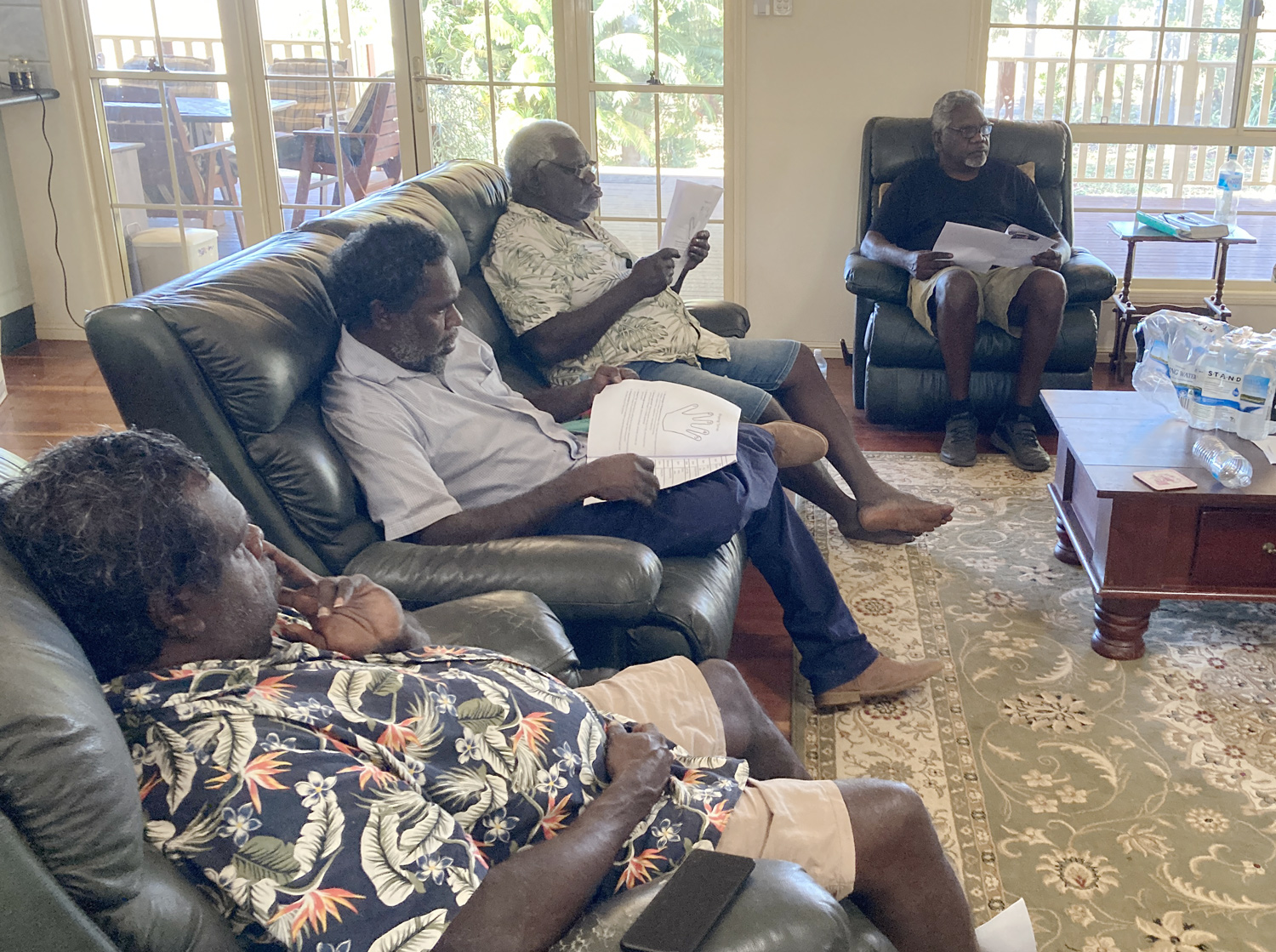

A men’s Bible study.

Over a year ago, I was travelling in Arnhem Land on the fringe of the Wet season. I had hopes of reaching a community to do various bits of planning with church leaders, but heavy rain and flooding resulted in me having to stay in a different community.

That evening, I joined the local church mob for their Bible study night. The Bible was read, and questions and discussion ensued in high pace Australian Kriol. I could just keep up.

A young man that I knew from a Bible Camp event a few months earlier arrived late to the Bible study.

Both of us had our Kriol Bibles open—I was struggling following the oral language, and he was struggling with the written words and which part of the passage people were referring to. He had not heard the passage read.

At the end of the study, we decided to read the passage together a bit more slowly. With my strong reading and his strong oral Kriol, we stumbled through the passage—him correcting my Kriol pronunciation, me helping him as he slowly sounded out the words. Laughing and correcting each other we read the passage three or four times until we had it right.

One way to think about this story is that we used our strengths to read the Bible in Kriol. But a better way is to recognise our vulnerability in the situation.

My vulnerability in language and his vulnerability in literacy meant in that moment of reading the Kriol Bible together, we needed to trust each other, in our mutual vulnerability.

This is an example of what church support workers call ‘vulnerable mission’, and educators describe as ‘two-way’ or ‘both ways’ learning. Both approaches prioritise mutuality, respect and humility in mission and ministry partnerships.

Please continue to pray for Aboriginal Christians and church leaders in the Northern Territory, and for God to raise up and train church support workers who are sensitive to contextual mission, and can help without hurting.

Header image: Nungalinya and CMS men: Derek, Craig, Edwin, Josh, Simon, Darryn and James

GO

![]()

Could you be someone who goes to support and care for the Aboriginal church in North Australia? Go to here to start a conversation with your CMS branch today.

- Corbett, S. and Fikkert, B., 2014. When helping hurts: How to alleviate poverty without hurting the poor… and yourself. Moody Publishers.

- Elmer, D., 2006. Cross-cultural servanthood: Serving the world in Christlike humility. [audiobook] InterVarsity Press. Available at: Audible. Chapter 12, [00:4:12].

- Williams, D. (2018) ‘Every Church Member as a Missionary’, CMS Checkpoint Magazine. Available at: https://cms.org.au/stories/every-church-member-as-a-missionary/ (Accessed: 10 December 2024).

- Mackenzie, J., 2022. ‘An Evaluation of Patron-Client Relationships in Australia Indigenous Cultures’, Evangelical Missions Quarterly, 58(1), pp. 28-32.

- Williams, D. (2015) ‘5 Tips for New Missionaries’, CMS Checkpoint Magazine. Available at: https://cms.org.au/stories/5-tips-for-new-missionaries/ (Accessed: 10 December 2024).

- Mackenzie, J., 2022, p30

- Van Gelderen, B. and Guthadjaka, K., 2021. Renewing the Yolŋu ‘Bothways’ philosophy: Warramiri transculturation education at Gäwa. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 50(1), pp.147-157.

- Elmer, D., 2006