Identity and Mission. Article Five of Six: Identity and Hybridity

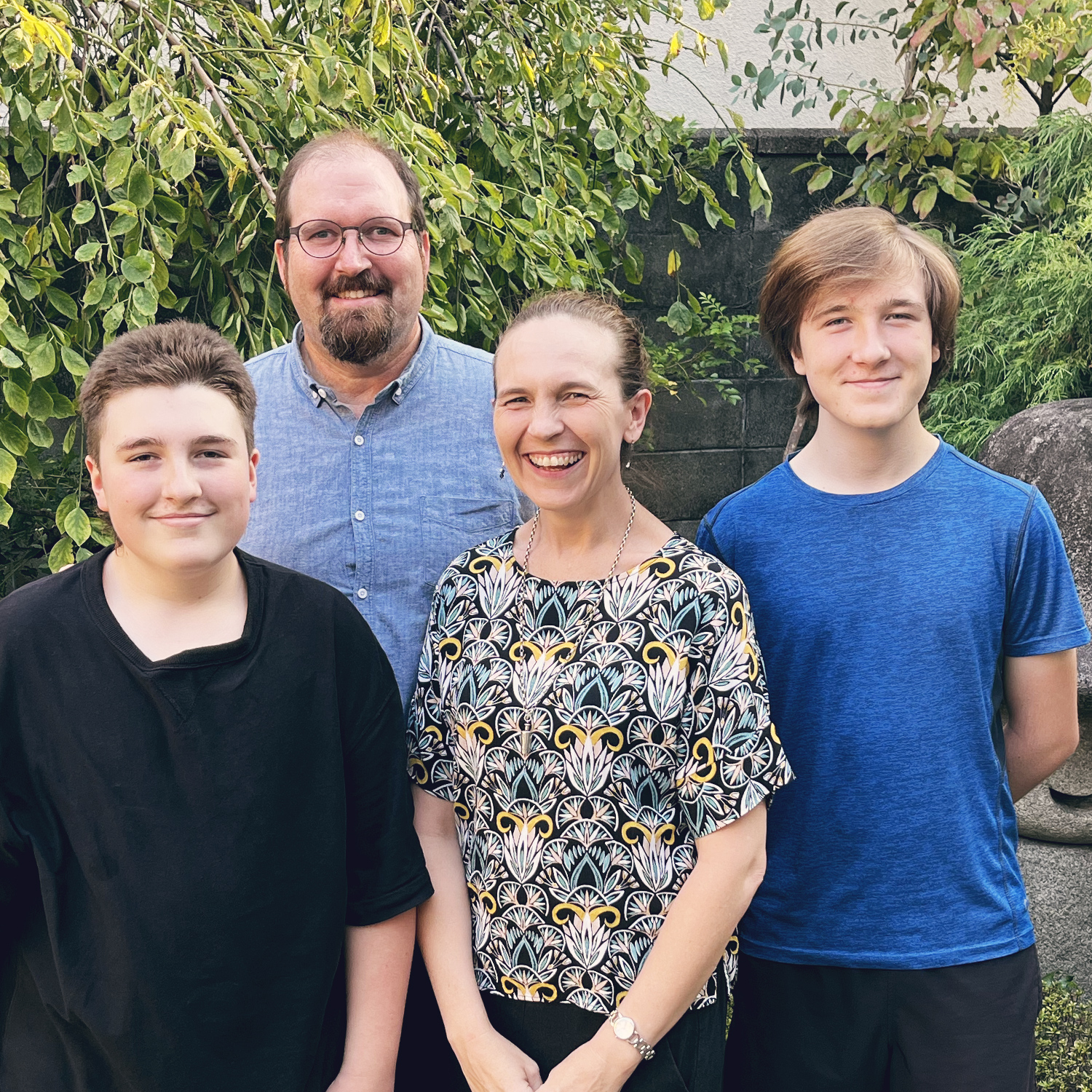

David Williams is Director of Training and Development for CMS. In this the five of six articles on ‘Identity and Mission’, he introduces his topic with some reflections on ‘Identity Crisis’. Article 1, ‘Identity Crisis’, is here. Article 2, ‘Identity and Mission’, is here. Article 3, ‘Identity and Scripture’, is here. Article 4, ‘Identity and Contextualisation, is here.

This is the fifth in a series of articles looking at the theme of identity in mission. At the end of the last article I wrote that mission needs to engage with the fundamental identity questions that believers from other religious backgrounds are asking. I suggested that we broaden the identity question from ‘who am I?’ to ‘who am I becoming and who do I belong with?’ And then to say: ‘I am becoming cruciform and I belong with a cruciform people.’ In this article I will explore these ideas in relation to the theme of hybridity.

Hybridity explained

Hybridity is a concept that has emerged in anthropology and post-colonial studies, borrowed from biology where two species are “cross-pollinated to form a third hybrid species.”[1] Hybridisation is therefore about the blending of cultures to create new cultural forms and meanings. Originally, hybridity was used to refer to the way that cultural identity was created during the impact of colonisation. Bhabha argued that as the coloniser and the colonised interacted, new cultural expressions emerged that drew from both parties – and that these forms emerged in what Bhabha called “a third space”.[2] The third space is an in-between, liminal space in which culture is created and given meaning. We are most familiar with the language of third space from the way that it has been co-opted to describe third culture kids – those whose passport tells them they Australian, who have grown up all their lives in Tanzania (or wherever) and who inhabit a third space between the two, creating their own hybrid identities.

Hybridity as applied to church

Let me adopt the language of hybridity and the third space and apply these ideas to the church.[3] I suggest that each local church occupies a third space. It exists between, on the one hand, the space of the surrounding culture and on the other hand, the space around Christ’s throne in glory, its eschatological identity. It exists as a third space, neither fully in the surrounding culture nor yet in glory, but something in between and therefore always partial and incomplete. For a local church and its members to find their identity in the third space will always involve the tension and incompleteness that are an innate part of hybridity. As disciples of Jesus on earth, we will always be a hybrid. In some ways, being a hybrid is frustrating: I am neither this nor that, I am not sure where I belong, different parts of me conflict with one another. On the other hand, being a hybrid is reassuring: I am unique, I can construct an identity out of my variegated history.

Churches in Australia are increasingly aware that they exist in a third space. As Christendom crumbles, it is self-evident that the wider culture we inhabit is not Christian, if it ever was. This reality has caused much soul searching, with frequent use of the exile and pilgrim metaphors – David Starling wondered if exile was the flavour of the year in 2016.[4] However, as Kate Harrison Brennan argues, we are only exiles in the sense that all disciples of Jesus Christ are exiles—to say that we have recently become exiles denigrates the experiences of those who have been forced out of their homes and countries.[5]

Hybridity and identity in Christ

How do the themes of hybridity and the third space help us as we think about what it means to have our identity in Christ, addressing the questions who am I, who am I becoming and who do I belong with? Finding my identity in Christ is a life-long journey. While I am no more ‘in Christ’ today than I was on the day of my conversion, my understanding of what it means to be “in Christ” has changed considerably, and no doubt need to change a great deal more. So I will always be a hybrid, living in a third space, travelling from the slough of despond to the celestial city,[6] and I will always belong with a hybrid people. Occupying the third space and living as a hybrid means that our identity in some senses will never be fixed. It will always be growing and changing as we grow closer to the celestial city and as the slough of despond keeps changing beneath our feet. The nature of this growth and change, however, needs to be cruciform – it must be shaped by and like the cross. As we live the life of a hybrid people in the third space, our hybridity must be defined by the cross, because it is the cross that connects the slough of despond to the celestial city.

Applying this practically

This all sounds very airy-fairy. So let’s get practical. How might this help us to disciple a new believer who wants to follow Jesus Christ and has been converted in a majority Muslim context? We might encourage the new believer that by faith they have been united with the Lord Jesus Christ and they now belong to Him. If they are truly in Him, nothing can snatch them out of His hand. We might say that belonging to Christ also means belonging with others who belong to Him, although the Bible doesn’t prescribe a specific form of what this looks like. We might say that working out what it means to belong to Jesus and with his people is a complicated thing to think through, and is likely to keep growing and changing over time.

However, the process of thinking through these complex issues must be informed by God’s Word as His Spirit teaches us; it must be done with God’s people; and it will be shaped like the cross, meaning that we should not expect the journey to feel comfortable and easy. As a discipler of this new believer, I cannot answer their identity questions for them. I can enable them to ask the right kind of questions. I can enable them to bring God’s Word to bear on the issues that face them. I can connect them with others who are travelling on the same road. And I can guide their expectations about what kind of answers they might be looking for and what this might feel like, which will be cross-shaped. I will expect some confusion in the hybridity of the third space, but also much growth.

We will think more deeply about the themes of identity and discipleship in the next and final article.

References Cited:

Ashcroft, Bill, Gareth Griffiths, and Helen Tiffin. Postcolonial Studies: The Key Concepts. 3rd ed. New York: Routledge, 2013.

Bhabha, Homi. The Location of Culture. New York: Routledge, 1994.

Bunyan, John. The Pilgrim’s Progress. Nashville, TN: B&H Publishing, 2017.

Harrison Brennan, Kate. “Finding Common Ground: A Contemporary Challenge for the Church.” In Anglican Institute Annual Lecture. Ridley College 2018.

Starling, David. “Are Christians in Exile?” Eternity, August 2016 2016, 17.

[1] Bill Ashcroft, Gareth Griffiths, and Helen Tiffin, Postcolonial Studies: The Key Concepts, 3rd ed. (New York: Routledge, 2013).

[2] Homi Bhabha, The Location of Culture (New York: Routledge, 1994).

[3] By “church” in this context I mean a local gathering of believers – see Article XIX of the 39 Articles.

[4] David Starling, “Are Christians in Exile?,” Eternity, August 2016 2016.

[5] Kate Harrison Brennan, “Finding Common Ground: A Contemporary Challenge for the Church,” in Anglican Institute Annual Lecture (Ridley College 2018).

[6] John Bunyan, The Pilgrim’s Progress (Nashville, TN: B&H Publishing, 2017).