Identity and Mission. Article Six of Six: Identity and Discipleship

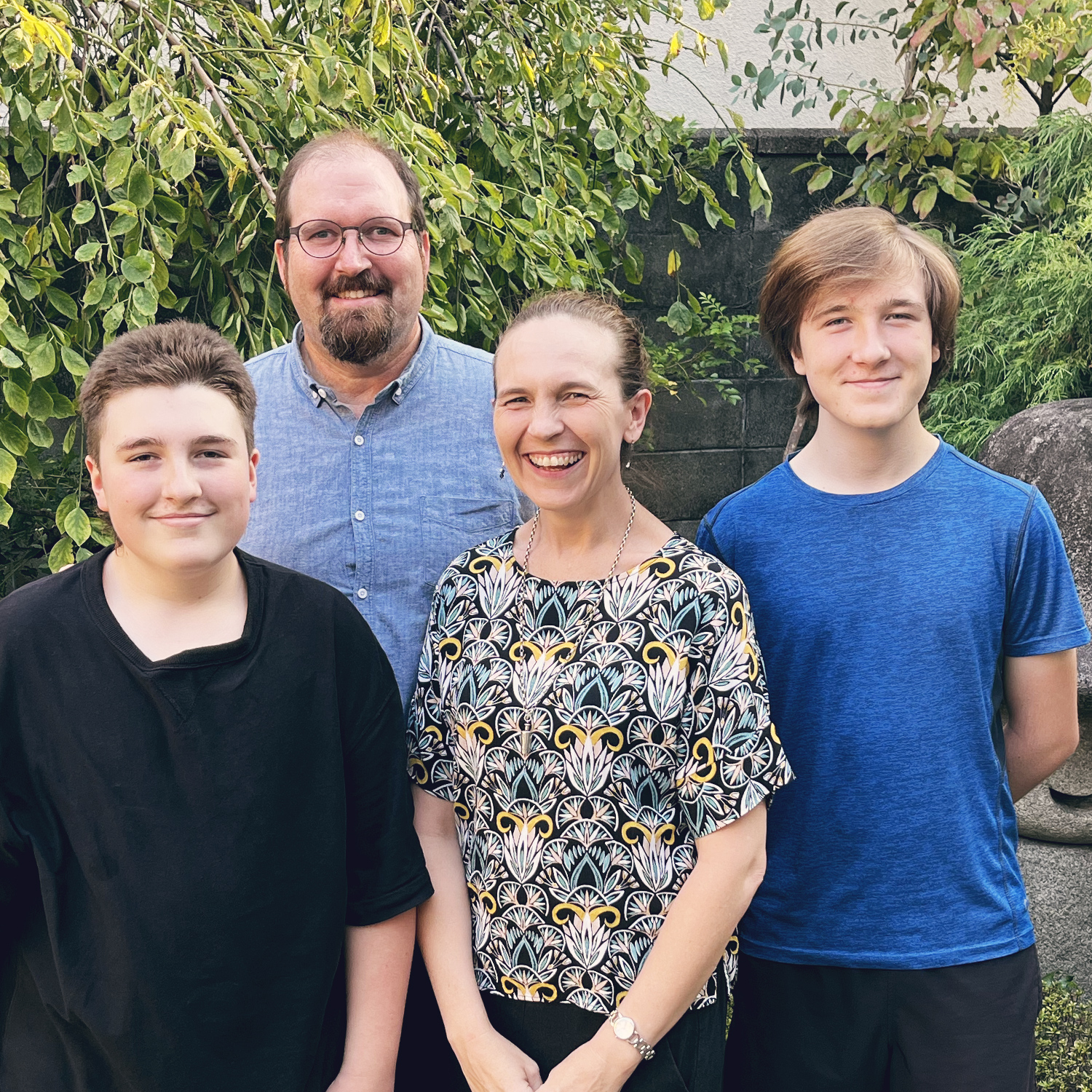

David Williams is Director of Training and Development for CMS. In this, the final of six articles on ‘Identity and Mission’, he summarises the previous articles and applies them to cross-cultural discipleship. Article 1, ‘Identity Crisis’, is here. Article 2, ‘Identity and Mission’, is here. Article 3, ‘Identity and Scripture’, is here. Article 4, ‘Identity and Contextualisation, is here. Article 5, ‘Identity and Hybridity’, is here.

In the final article in this series, I will summarise the themes we have been exploring and apply them to the context of cross-cultural discipleship. I have suggested that helping people to find their identity in Christ is a core task in mission. This is especially challenging for those who come to know Jesus from a majority-other-faith background. Identity is a complex thing, both given and constructed, and is deeply embedded in our social relationships. Our identity in Christ is also both given and constructed, and also has a powerful social dimension to it. My identity in Christ is inescapably an identity with Christ’s people. Therefore, having an identity in Christ is about who I am, who I am becoming and who I belong with. The New Testament gives remarkably few cultural descriptions about what this identity in Christ and with His people looks like – except to say that it is given in the gospel, is constructed in gospel relationships suffused by holiness, love and grace, and that its shape is cruciform. To be in Christ is to be united with Jesus in his death and resurrection. This means that my life must become cross-shaped and that I belong with a cruciform people. Becoming cross-shaped and belonging with a cruciform people will always be a hybrid thing, as a local church occupies an in-between space, between the slough of despond and the celestial city.

How, then do we disciple someone like the Buddhist-background friend I mentioned in the first article? He has formed his identity out of the traditional markers of race, ethnicity, nationality, culture, gender, family, relationships, role and religion.[1] For him, these markers together create an identity he calls ‘Buddhist.’ Changing one out of eight of the markers, the religion marker, has not yet changed the label he uses to describe himself. So what will I do? Let me suggest four aspects to my engagement with him.

Four aspects to engagement

First, I’ll begin by not panicking, recognising the reality of hybridity. Identity is both given and constructed, so it will take time to find an identity in Christ. I must accept that there will always be hybridity, perhaps more than I would like or feel comfortable with.

Second, remembering that my identity in Christ is given in the gospel, I will want to ensure that my friend deeply understands and appropriates the gospel and all that Christ has achieved for him on the cross.

Third, remembering that my identity is constructed in the context of social relationships, I will want to link my friend with other believers; and I will want him to find ways of talking about his new faith with his existing social networks, if this is possible.

Fourth, remembering that my identity in Christ is cruciform, I will not expect easy answers, but will encourage him to take up his cross to follow his Saviour.

Mining and connecting

In reality there are two key activities that sit behind these strategies: mining and connecting. We need to mine God’s Word with our newly believing friend and help them to discover what Scripture teaches them about being in Christ. We cannot tell them what their identity should be, but we can help them discover their identity. This is a work of God’s Spirit through God’s Word, where our role is to keep opening the Bible with people and bringing them back to the centrality of the gospel, to the themes holiness, love, grace and cruciformity, whilst recognising the reality of hybridity. Let me give a specific example: if a new believer is asking “what should my attitude towards my family be?” this question might be motivated by a desire to respect and honour their parents, or by a desire to avoid rejection and hardship. The principles of holiness and cruciformity will suggest different answers to each of those motivations. Meanwhile, the principle of hybridity will help us to remember that our answers to these kinds of questions always have a degree of provisionality to them and may well change as we grow and mature. Since my identity is hybrid, I can focus on what I am becoming.

So we mine God’s Word with people, helping them to create an identity defined by holiness and cruciformity. But we remember that identity is also socially constructed. So we need to connect the new disciple to others who are following Jesus, ideally by connecting them to local gatherings. The quality of relationships within these gatherings will be critical if a new disciple is to find their identity in Christ. These gatherings also need to be characterised by holiness and cruciformity. The significance of the labels attached to these gatherings (Christian, Presbyterian, Follow of Isa etc.) is not nearly as important as the character of the relationships within them. We will also encourage them, where this is possible, to connect their faith to their existing social networks. I cannot prescribe what this connection will look like or when it will happen, but I can keep exploring its possibility.

Quality of relationships in church is critical

In a seminar at GAFCON in 2018, Rev Yee Ching Wah from the Diocese of Singapore talked about his experience of church planting in Thailand. He said that people needed to be discipled before they were evangelised. What he meant by this was that the Thai person considering faith in Christ needed to see what a Christ-following life looked like before they would commit to it. For example, they needed to see what it looks like for Thai disciples of Jesus to honour their parents, to respect the King and so on. If they could see these things being done well, then they were much more likely to make their own commitment to follow Jesus.

Since a significant part of our identity is socially constructed, it makes sense that we see what the social relationships in a new group look like before we commit to becoming part of it. The quality of relationships in a local church will therefore be a critical factor in making the gathering attractive to outsiders. Our relationships within our local churches need to reflect more of the Celestial City than the Slough of Despond (read John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress!)—to be shaped by the gospel and characterised by holiness, grace, love and cruciformity. In post-Christendom Australia, where God’s people are increasingly considered a force for harm in society, the visibility and quality of our social relationships could hardly be more significant:

12 Live such good lives among the pagans that, though they accuse you of doing wrong, they may see your good deeds and glorify God on the day he visits us. (1 Peter 2:12)

References Cited:

Rosner, Brian. Known by God: A Biblical Theology of Personal Identity. Biblical Theology for Life. Edited by Jonathan Lunde. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2017.

[1] Brian Rosner, Known by God: A Biblical Theology of Personal Identity, ed. Jonathan Lunde, Biblical Theology for Life (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2017), 41ff.