Reforming mission, reforming hearts

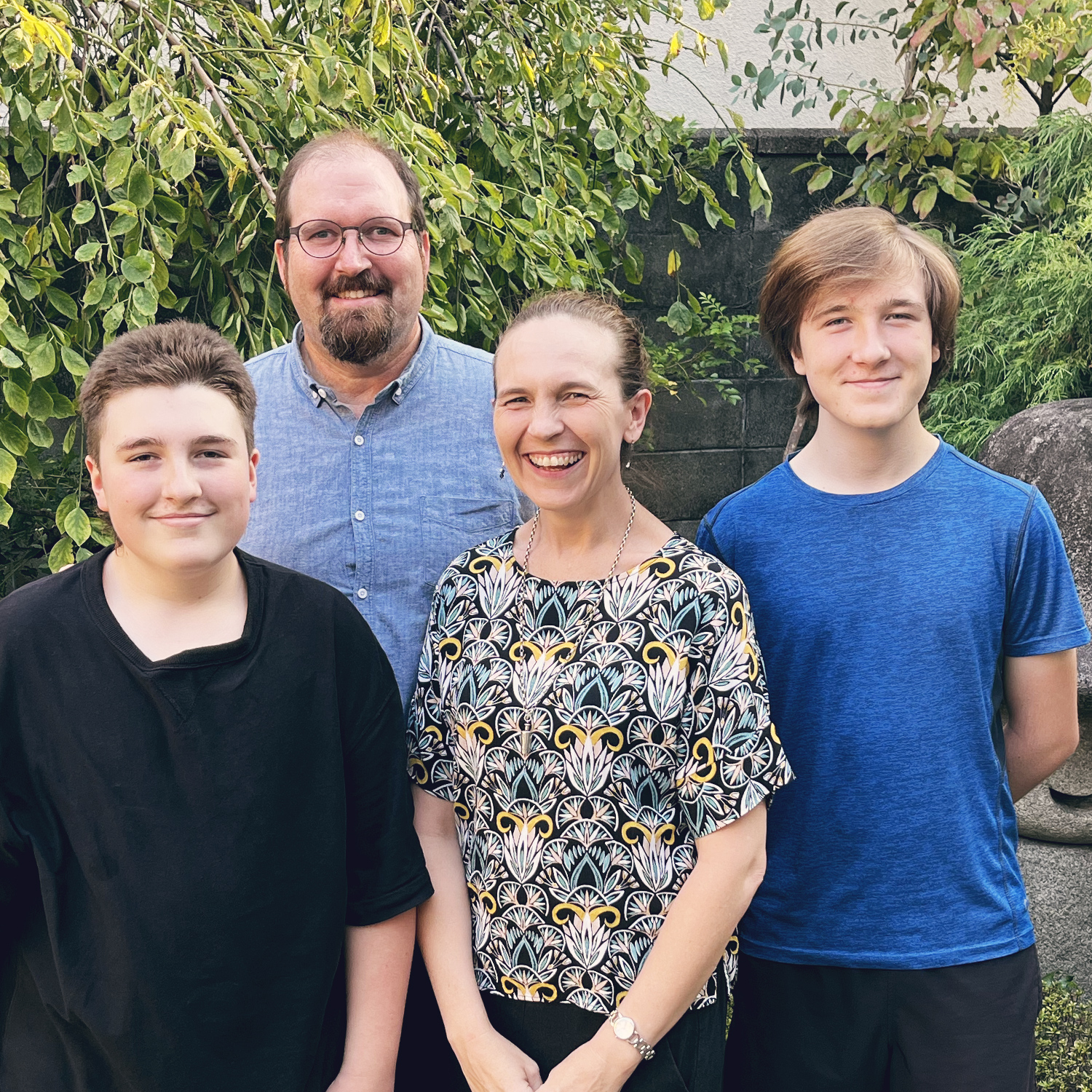

CMS missionary Mark Dickens teaching the Bible in Singapore.

Does the Protestant Reformation have any relevance to how and why we do mission today? Rhys Bezzant, Dean of Missional Leadership at Ridley College in Melbourne, explains why the answer is a resounding yes.

500 years ago on October 31 (if these things can ever be dated so precisely), the Protestant Reformation began. It is usually said to have started on the day when German monk, Martin Luther, publicly nailed his 95 theses to a church door in Wittenberg and so opened a discussion on how we could be right with God. Essentially, he argued that righteousness in God’s sight was a free gift, and so denied that this righteousness could ever be bought with money.

Right with God

Luther had become increasingly convinced, through his reading of Romans, Psalms, Genesis, Galatians and the writings of Augustine, that this righteousness, or justification, could only be received as a free gift of God, through faith in Jesus Christ—hence the great Reformation slogan, ‘justification by faith alone’. Justification is God’s declaration that we are righteous in his sight:(1) God the perfect judge of all declares that we are not guilty—completely innocent of any wrongdoing or sin—not because of anything we have done, but only by trusting in the death and resurrection of the Lord Jesus on our behalf.

Luther’s first and fundamental concern was personal rather than academic in nature. Although he was a scholar, he wasn’t setting out to make an academic name for himself by discovering new theological insights in the newly created university of Wittenberg. Nor was he motivated by any radical desire to overturn medieval church and society and start from scratch. He did not force Church reform; rather the role of ‘reformer’ was forced on him by his reading of Scripture.

Luther’s basic quest was to find consolation for his anguished soul, for he had grown up with a view of Christ associated with terror, not tranquility. He assumed that the righteousness of God meant God’s just condemnation of guilty sinners like him—hence his terror at the idea of meeting Christ as his judge. Yet, as he read his Bible, it slowly dawned on him that he could know with deep assurance that he was indeed justified by faith alone. No wonder that in response to this discovery he resisted the pressure of the Emperor and the Pope to recant his views: he had become absolutely convinced, from his reading of Scripture, that free forgiveness could belong to him and to all who trusted in Christ.

Because of this, Luther’s Reformation was, at heart, missionary in nature. He wanted everyone to know the precious transforming power of the grace of God.

The Bible for the people

Fundamental to this missionary endeavour was the translation of the New Testament out of the original Greek and into an easily understood German, for that was how the average German could read for themselves of the grace of God. There could be no better or more sustainable way to present the gospel to regular citizens than to give them a German Bible for use in church services and at home. Luther also wrote prefaces to each book of the Bible to make sure that the theological implication of each book was patently clear.

There had been translations of the Bible into German before Luther, based on the Latin translation of the Bible. Luther worked instead with the best available versions of the original Greek and Hebrew texts of Scripture. Not only this, but the kind of German he used, the dialect of the Saxon court, was accessible to Germans in the north, south, east and west of the country. In this way, he was uniting Germany around the Bible at the same time as he was renewing the Church. It is exactly the same impulse—to unite people around the truth of God’s word by giving it to people in their own heart languages—that leads CMS and other mission organisations to continue the work of Bible translation and teaching today.

But Luther’s aim was not merely to publish—as if he might lose a tenured position at the university if he did not! The reason he published books, tracts, Bibles and sermons was to get the gospel out to lay people, many of whom were sitting in churches ignorant of the Bible’s teaching. His was a church-going world, although the commitment of many was nominal. The problem was not that the gospel had vanished from the Church, but rather that it had been obscured, confused, or veiled. Luther’s ministry was therefore occupied with making gospel proclamation clear, concise and coherent. Although employed as an academic, he devoted much energy to preaching in local churches, writing catechisms to train the young, composing letters to encourage the downhearted, and mentoring young leaders around his dinner table. He worked and prayed for the gospel’s advance.

Bible-based reform means mission

It is true that unlike CMS, Luther did not send missionaries to Asia. He did not even set up a mission agency to raise money to support cross-cultural workers. Other Reformers, like John Calvin, did train leaders in Geneva to send back to the Reformed Church in France, and were even involved in sending people to Brazil. But without the means for global travel, this kind of mission was always going to be the exception and not the rule.

What Reformers like Luther in Germany, or Calvin in Geneva, or William Tyndale in England achieved, however, was to respond to the great missionary challenge of their own world: namely to preach the gospel in a language that was easily understood, and to work to make sure that this message was reaching the human soul, where it could offer consolation, peace and joy.

This is why, at its heart, the Reformation message of ‘justification by faith alone’ is thoroughly missionary in its intent. Everyone needs to hear this message loud and clear, not just academics or a select priestly class. The great sixteenth-century Reformers were concerned with telling and teaching the gospel in local churches, in universities, in towns—wherever there were people who needed to know that their sins could be forgiven by the grace of God alone. That need continues today. Whether we live in Melbourne, Mexico City, Manila or Marseilles, there is much confusion today about the gift of grace, and much need to pursue the work of gospel proclamation in the twenty-first century. The Reformation is not yet over!

GIVE

To make Jesus known worldwide, CMS is committed to training gospel leaders. Providing scholarships is one way we are meeting the need for gospel clarity. Go to cms.org.au/trainingleaders to support this great ministry so that CMS can continue training and equipping students overseas to teach the Bible faithfully.

1. In the Greek of the New Testament, the terms ‘justified’ and ‘made righteous’ are one and the same word.↩